Inequitable ideas about manhood and masculinity are alive and well.

Restrictive, inequitable, and stereotypical views of men’s and women’s roles are highly prevalent across IMAGES settings. IMAGES assesses ideas about traditional masculinity and masculine norms as a primary focus, and this section explores three statements in particular: “A man should have the final word about decisions in his home” (power); “A woman’s most important role is to take care of her home and cook for her family” (household gender roles); and “A woman should tolerate violence in order to keep her family together” (violence).

IMAGES data show that men in the Arab States have consistently traditional and inequitable ideas about gender, with Egyptian men most committed to all three measures of traditional or restrictive manhood, and Lebanese men the least, particularly with regard to tolerating violence. Men in sub-Saharan Africa appear to hold traditional ideas of masculinity overall, but Mozambique is an interesting exception, with distinctively lower levels of traditional, restrictive attitudes across all three measures. Men from South Asia and from East Asia and the Pacific share similar attitudes, with a strong emphasis on the importance of maintaining inequitable gender roles.

Women in the five regions for which we have data are far less likely to hold consistently traditionalist views, except in sub-Saharan Africa, where women show the greatest agreement with men on the three dimensions of traditional gender roles. Women in South Asia largely agree with stereotypes regarding gendered power and roles but do not feel women should tolerate violence from male partners. Women in the Arab States, like men in the region, have the most consistent adherence to all three dimensions of traditional, inequitable gender norms. Overall, however, it is traditional attitudes about roles and power that women and men are more likely to uphold, while women and men appear to be less accepting of the view that women should tolerate violence from a male partner.

What the figures show us is that gender traditionalism is alive and well, including support for maintaining inequitable gendered roles, men’s domination in decision-making, and justification of violence against women. At the same time, though, these attitudes vary substantially and point to opportunities to shift gender norms by building on change that is already happening.

Younger men rarely have more gender-equitable attitudes than older men do

Alongside recent increases in the global discourse about gender equality, one might expect to see a meaningful shift in attitudes about these topics over time. But do younger people actually hold more equitable views about gender than older people do? In an analysis of the three previously mentioned dimensions of gender attitudes (power, household gender roles, and violence), the answer for young women is mostly yes, while the answer for young men is sometimes but mostly not. For this analysis, a single measure of how gender equitable a person’s attitudes are was created from these three attitudinal measures. Respondents received a score of 1 for each of the three statements they disagreed with, for a scale score total of 0 to 3, with a higher number indicating more equitable views.

Among men, age cohort is significantly correlated with the combined attitude score in 16 studies. To be sure, in select locations such as Georgia, Lebanon, Chile, and Cambodia, younger age cohorts consistently hold more equitable scores. More often than not, though, this significant relationship seems to show that men’s attitudes follow a curved pattern, whereby the oldest and the youngest men hold more restrictive views than those in their early 30s.

Among women, however, the relationship is more consistently positive across all age groups. As a whole (with the exception of Uganda), the directionality is clear: Younger age groups of women hold significantly more equitable views than older age groups do, especially when taking an average of the 12 studies in which this relationship was statistically significant.

Younger men’s restrictive gender attitudes seem consistent during an era of backlash against the progress of women’s movements and amid the rise of anti-feminist political leaders, a pushback against the women’s rights agenda, and in some countries, “men’s rights” and male supremacist groups, particularly in online and social media spaces frequented by young people. We can also hypothesize that the youngest groups of men – especially those not yet partnered or raising children – hold idealized or hypothetical notions of their (future) roles in heterosexual relationships, while men with the lived experience of cohabitating and cooperating with their partners have come to a slightly more equitable worldview. Regardless, this pattern questions the idea that the younger generation of men is more likely to buy into gender equality. For many younger men in some settings, the case must still be made for why gender equality is urgently needed and has not yet been achieved, which presents a serious challenge for policymakers, activists, and educators alike.

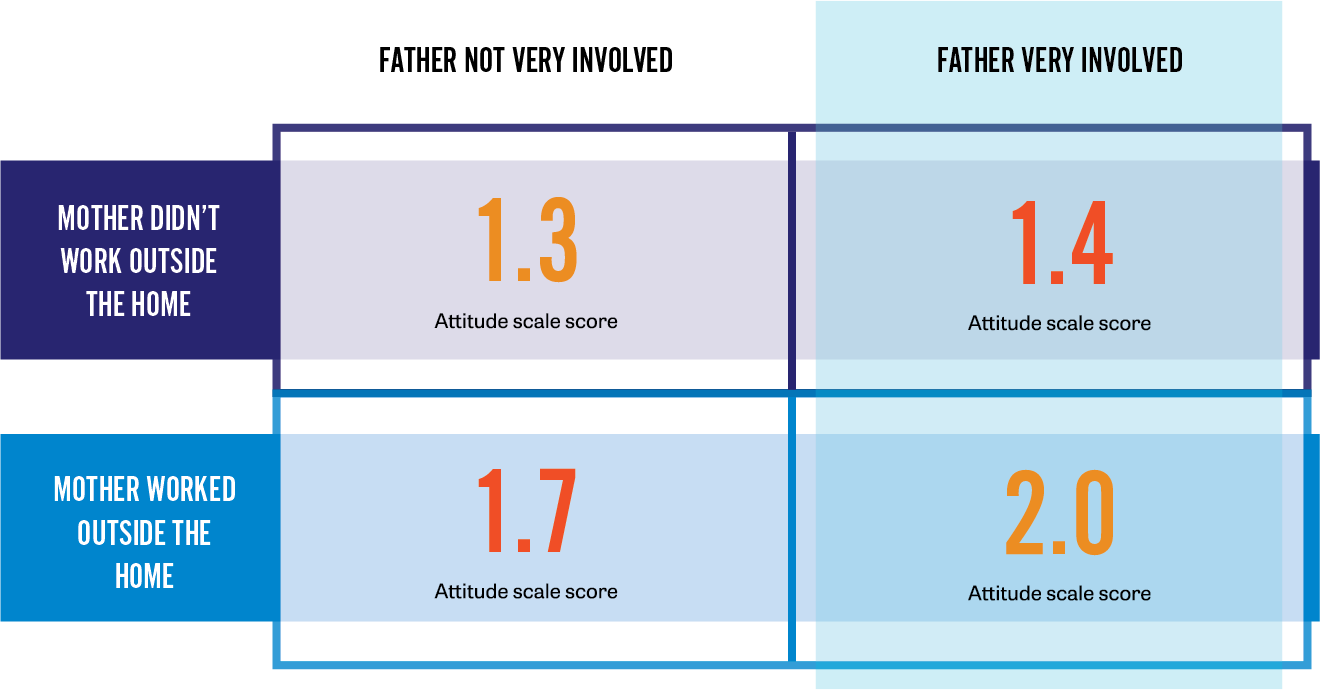

Women and men who grew up seeing gender equality in their households as children hold more equitable attitudes.

In IMAGES data, men who saw their fathers heavily involved in household work tend to hold significantly more gender-equitable attitudes. Kuwait, Azerbaijan, and Tanzania stand out as countries where the difference between the gender attitudes of men who did or did not have involved fathers is particularly large. Similarly, women who saw their mothers working outside the home have significantly more gender-equitable attitudes. In each case, behavior by the same-sex parent that went against the gender stereotype had lasting effects in the attitudes of their children. To be sure, there are “exceptions that prove the rule”; in India and Indonesia among men and Afghanistan among women, these relationships are statistically significant, though not at a high real-world magnitude, in the opposite direction. Yet by and large, we find that the legacy of nontraditional gendered behavior on the part of parents lives on in the attitudes of their children. Of note, it may be that women are more likely to report their mothers working because, in general, they paid more attention to their mothers’ roles inside and outside the home as they assessed their own future prospects and life trajectories, whereas boys might have paid more attention to their fathers’ trajectories and behaviors.