Though sexual and reproductive health and rights are often viewed as "women's issues," men are participating.

Although sexual and reproductive health tends to be viewed as women’s domain, the global data show that men are often supportive and active in decision-making about contraceptive use and antenatal visits, as well as in decision-making on and actions to terminate a pregnancy. They also are often present during labor and delivery. IMAGES includes four measures on these issues for both women and men. With regard to who has the final say in contraceptive decisions, women report 65 percent of those decisions are shared equally, while for men, this figure is 75 percent. However when the “shared equally” category is added to the response that she has the final say, the total is very similar: 86 percent for women and 85 percent for men. Similarly, looking at whether a male respondent – or a female respondent’s male partner – provided financial support for an abortion, 65 percent of women and 69 percent of men say he did.

Traditional gendered views about sex and reproduction contribute to poor sexual and reproductive health by impeding communication and creating unstated expectations and pressures. A look at men’s responses to three attitudinal questions related to sexual and reproductive health and rights shows some of the gendered expectations underlying this area. Men’s responses to “It is a woman’s responsibility to avoid getting pregnant” and “I would be outraged if my wife asked me to use a condom” vary considerably. At the same time, men around the world show high levels of agreement with the statement “Men need sex more than women do” – including more than half of men in 11 of the 20 countries for which data are available on this measure.

Adhering to inequitable gender attitudes is bad for men's health.

IMAGES is centrally interested in exploring the links between traditional masculinity and practices that are harmful to men’s health, including risk-taking, substance abuse, and avoidance of seeking care. In some societies, men are expected to remain strong and keep going even when they are sick or injured. This expectation makes men less likely to seek medical or other forms of help when they need it. Traditional masculinity can also drive men to take risks, and around three-quarters of global deaths from road crashes occur among boys and men. In various societies, masculine norms suggest that men should be knowledgeable and dominant in their sexual activities. These expectations encourage men to have multiple partners, avoid conversations about contraceptive use, drink alcohol, smoke, and maintain other unhealthy practices.

Men with more restrictive gender attitudes engage in more binge drinking, with the association between more restrictive views of gender and more binge drinking being significant and remarkably consistent across Latin America and the Caribbean, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Men with more inequitable attitudes are also more likely to report feelings of depression, as reflected in yes/no answers to the question, “Are you feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?” And some men with more traditional attitudes more frequently engage in poor health-seeking behavior: They often have not sought any health services for themselves within the past two years, a very low bar indeed. Yet these data show that there are other men for whom gender-traditional attitudes are associated with greater likelihood of seeking out health care. This may reflect a prioritization of the self prevailing over the sense that a “real man” does not need to go in search of help with his health. The high number of countries for which the significance is the reverse of what was expected also indicates that attitudes are not the only driver of men’s poor health-seeking behavior; other important factors include men’s working lives (their exposures and the flexibility of their time) and the availability of health services.

Stresses and fears related to providing financially and protecting the family are widespread.

The expectations that men should be breadwinners are strong and pervasive. Men often pin their identities on this financial provider role, but in many economic circumstances, this is impossible. Men face pressures to conform to this role from peers and family, including intimate partners, and their ability to fulfill the role can determine their eligibility for marriage and their satisfaction and stability within that marriage. Men perceive this pressure to be providers even in divergent settings with financial crises, war, displacement, or high unemployment rates. Although the “provider” identity is expected of all men, structural forces outside their control often curtail their opportunities to fulfill the role.

The IMAGES survey includes a question to assess agreement with the statement “I am frequently stressed or depressed because of not having enough work or income.” While there is wide variation, the overall results show this “provider” identity stress is very common: 61 percent of men overall affirm this stress, and the rates are above 90 percent in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Nigeria, and Chile and extend as low as 17 percent in Kuwait. As a region, the Arab States shows consistently lower work-related stress among men than other regions.

Yet when people from the region were asked whether they agreed with the statement “I worry about not being able to provide my family with daily life necessities,” at least 60 percent of both women and men responded affirmatively, with the exception of Kuwait. While they may not have been stressed or depressed, men and women certainly feel the pressures of the role and worry about their ability to fulfill it. Indeed, women in Lebanon and Egypt were more likely than men to agree with the statement on being worried about providing for their families.

A complementary aspect of traditional masculinity is that a man must be the “protector” of his family. IMAGES measures this by asking whether women and men agree with the statement “I worry about my family’s safety.” In the midst of active political or armed conflict, the forces that risk the safety and livelihood of men and their families go far beyond anything under individual control. For example, over 95 percent of men and women in Palestine and Lebanon express worry about their families’ safety.

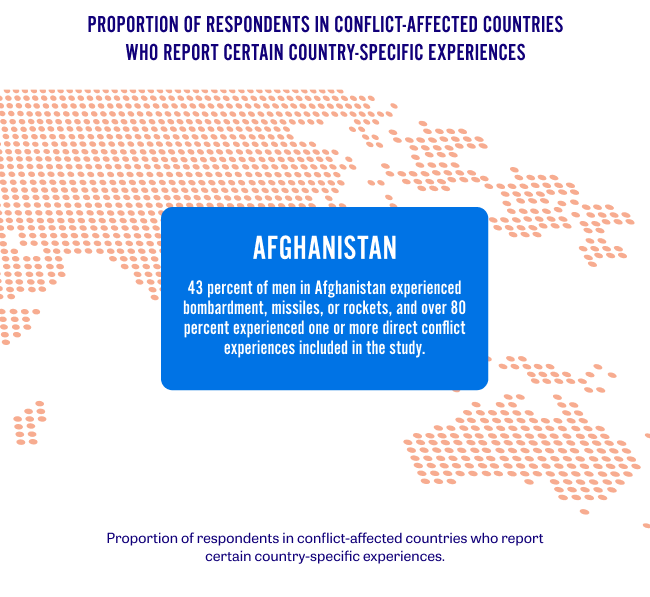

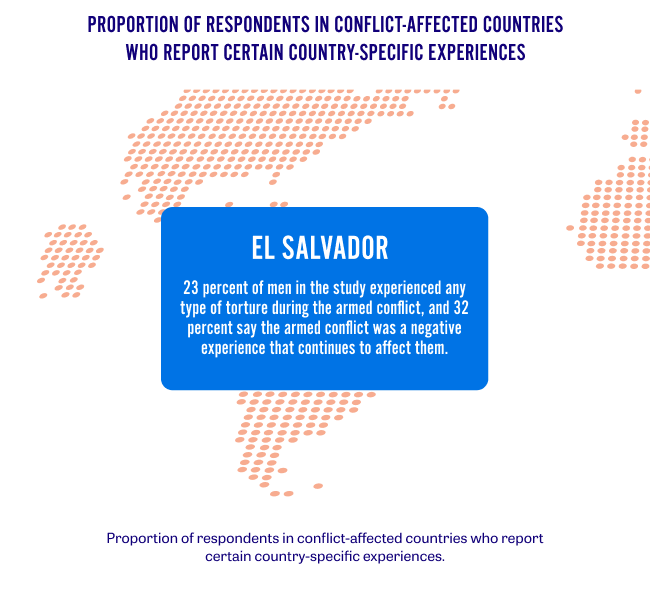

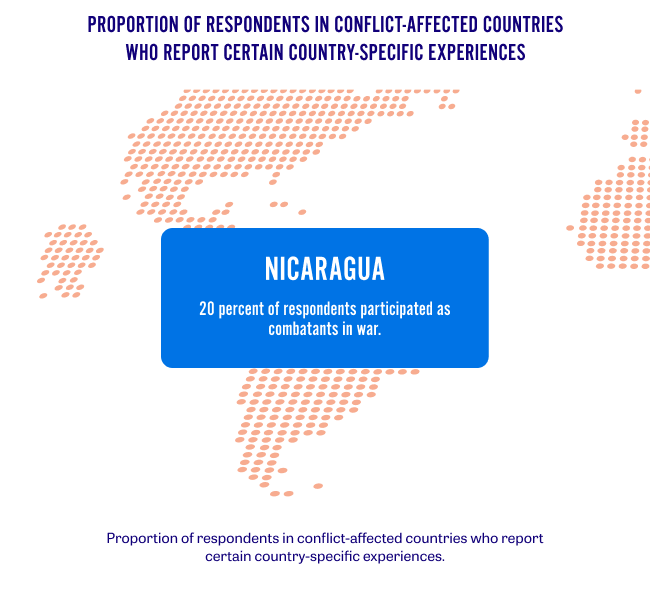

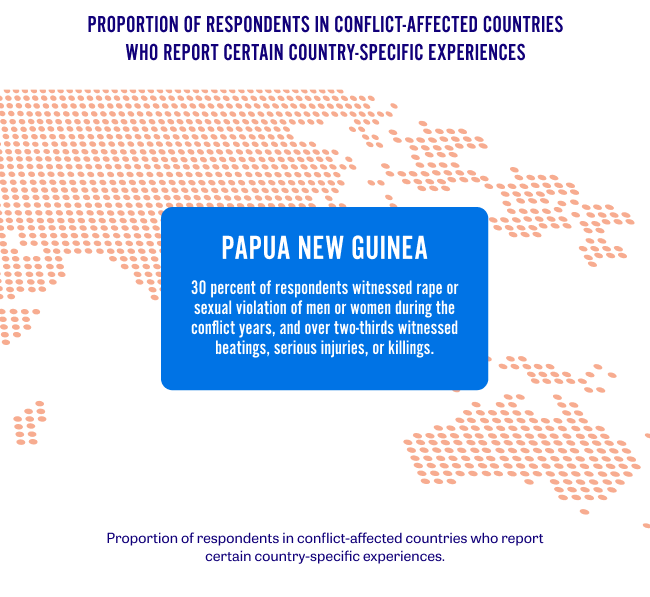

War, economic instability, and other major structural factors continue to shape men’s lives in extremely diverse contexts and make it difficult for them to achieve their desired roles as providers. The figure reports on the high percentages of men and their families exposed to direct conflict in seven disparate IMAGES countries. The experiences reported here highlight the impossibility of fulfilling traditional masculine roles under these circumstances. They also highlight the extent to which trauma is a reality in so many people’s lives. From personal experiences of physical violence cited by men in Afghanistan and El Salvador to witnessing killings and rape in Mozambique, Papua New Guinea, and Rwanda to active participation as combatants in Nicaragua and Serbia, conflicts have profoundly affected millions of men and women. There is little that they as individuals can do to alter the regional or global political and economic affairs that shape their lives.